After (Robert E.) Howard’s unfortunate suicide in 1936, readers still hungered for strong fantasy characters, and many incredible authors stepped up to fill the void. One of those was the masterful Henry Kuttner, who danced easily between fantasy, horror and science fiction. He wrote a quartet of stories about Elak of Atlantis, which were recently reprinted:

Below, I give a brief summary of the Elak stories, and some comparison to the Conan works of REH.

Kuttner wrote four Elak stories, which appeared in Weird Tales between 1938 and 1940. They serve as a sort of abridged version of REH’s Conan stories, and follow the exploits of Elak as he passes from sword-for-hire and no-goodnik to king.

My overall impression of the Elak stories is that they are not as well developed as the Conan tales. The setting of Atlantis is but a shadow of Howard’s Hyborian Age Earth, though there is at least a consistency in description which makes the land mappable (a map is included in the recent volume). We’ve discussed previously Kuttner’s collaboration with wife C.L. Moore; comparing their styles, one can see that Moore provided much of the elegance and descriptive power in their joint work. Comparing Kuttner’s fantasy to Howard or Moore, one finds that Kuttner is much more sparing in his descriptions. Details also seem a bit less thought out: the villain in the first story is named “Elf”, for pity’s sake!

Elak is accompanied by the perpetually drunk thief Lycon, who is loyal even when he is sneaking a few coins from Elak’s purse. He is occasionally joined by the druid Dalan, who uses his magic in service of Elak’s native kingdom, Cyrena.

Elak’s four adventures are summarized below:

"Thunder in the Dawn". Elak is rescued from an assassin by Dalan, who informs him that his brother, the king of Cyrena, has been overthrown by invading Vikings aided by the wizard Elf. The trio, joined by the feisty lady Velia, battle their way to the northern kingdom to return Orander to the throne. This tale reads remarkably like a bit of Dungeons & Dragons fiction, with a party of adventurers undertaking a journey to defeat evil.

"The Spawn of Dagon". Elak and Lycon are hired by a secretive society to kill the Wizard of Atlantis, who performs secret and sinister works away from prying eyes. But, as is often the case, things are not quite as simple as Elak first assumes.

"Beyond the Phoenix". Elak and Lycon, serving as guards of the king of Sarhaddon, fail in their duty! They are then tasked to take the king’s body, and his heir, on a journey along an underground river and through the Phoenix Gates, to complete an ancient ritual. Betrayal, and the clash of ancient powerrs, await them beyond the gates.

"Dragon Moon". Dalan yet again seeks out an unwilling Elak, this time to claim the throne of Cyrena. Elak’s brother Orander has been killed by a sinister and powerful being of unknown origin named The Pallid One. Now the Pallid One, occupying the body of a rival king named Sepher, marches to conquer Cyrena. Elak must unite warring tribes and nobleman against the forces of The Pallid One, and also learn the secret origin of the creature. This tale is very reminiscent of Howard’s “Conan the King” story, "The Hour of the Dragon", even having similarly-themed titles!

The Elak stories are excellent page turners, albeit a little clumsy in their execution. They can’t compare with Howard’s masterful prose (what can?) but are well worth reading for fans of sword-and-sorcery.

1946 was a very good year indeed for sci-fi's foremost husband-and-wife writing team, Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore. Besides placing a full dozen stories (including the acknowledged classic "Vintage Season") into various magazines of the day, the pair also succeeded in having published three short novels in those same pulps. The first, "The Fairy Chessmen," which was released in the January and February issues of "Astounding Science-Fiction," was a remarkable combination of hardheaded modernist sci-fi and almost hallucinatory reality twists. "Valley of the Flame," from the March issue of "Startling Stories," was an exciting meld of jungle adventure, Haggardian lost-world story and unique fantasy. And that summer, in "Startling Stories" again, the team came out with "The Dark World," a work that is pretty much a "hard" fantasy with some slight scientific leavening.

In this one, the American flier Edward Bond is whisked from the Pacific theatre during WW2 and transported to the eponymous Dark World, an alternate Earth that has diverged from its parent in space as well as time. His counterpart on the Dark World, Ganelon, head of a coven of mutated overlords who are busy keeping that realm subjugated, is sent to our Earth with Bond's memories. The book's plot is difficult to synopsize, and gets a bit complicated when Ganelon is brought back to the Dark World sometime later, his body now housing two distinct minds and personalities. Thus, the understandably mixed-up warlock can't quite decide whether or not to help his fellow "Covenanters" wipe out the forest-dwelling rebels, or join those rebels and destroy the Coven, not to mention the dreaded, sacrifice-demanding entity known as Llyr. Though called the Coven, Ganelon's fellows number only four, and include Medea, a beautiful vampire who feeds on life energies; Matholch, a lycanthrope; Edeyrn, a cowled, childlike personage whose power the authors choose not to reveal until the novel's end; and Ghast Rhymi, an ancient magus whose origin really did surprise this reader.

Peopled with colorful characters as it is, and featuring a nicely involved plot and ample scenes of battle, sacrifice, magic and spectacle, this little book (the whole thing runs to a mere 126 pages) really does please. That small scientific admixture that I mentioned earlier takes the form of rational explanations for the vampire, werewolf and Edeyrn phenomena; these explanations, while not exactly deep or technical, do tend to make the fantastic characters on display here slightly more, well, credible. But for the most part, "The Dark World" is a somber fantasy, and a darn good one, at that. Not for nothing was it selected for inclusion (as was "Valley of the Flame") in James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock's excellent overview volume "Fantasy: The 100 Best Books." "I consider the work of Henry Kuttner to be the finest science fantasy ever written," says Marion Zimmer Bradley in a blurb on the front cover of the 1965 Ace paperback (pictured above, and with a cover price of 40 cents) that I just finished, and readers of "The Dark World" will probably not feel inclined to give her argument. Roger Zelazny said that the Kuttner story that had the greatest impression on him when younger was The Dark World and remarked that much of its appeal comes from its "colorful, semi-mythic characters and strong action." He cited Kuttner (and C. L. Moore) as major influences on his work, noting that Jane Lindskold identified a number of specific influences from Kuttner and Moore in his own work, particularly the "Amber" chronicles. (Sandy, GoodReads)

Henry Kuttner (1915-1958) may be referred to as “one of the most important science fiction authors you’ve never heard of.” He was incredibly prolific and versatile, writing countless short stories of science fiction, fantasy, horror, thriller, and adventure, as well as over a dozen novels. Many of his works have been adapted into movies and episodes of television shows, including The Twilight Zone.

I recently came across a reprint of Kuttner’s novel Valley of the Flame (1946), and jumped at the chance to read it.

The story is a somewhat standard “lost world” adventure story, with a few twists. One of those can be seen on the cover of the book: the lost world, the titular Valley of the Flame, is inhabited by intelligent, hyper-evolved cat people!

The story begins in a remote region of the Amazon, where medical researchers Brian Raft and Dan Craddock run a small health center, researching tropical diseases. In recent days, drums have been sounding in the surrounding jungle almost continuously, putting Craddock — an older man with a mysterious past — on edge. He becomes even more nervous when a pair of strangers arrive, one deathly ill, the other somehow… different. Soon, the sick man is dead, and the unusual man has left with Craddock, apparently against Craddock’s will.

Raft goes in pursuit, and the trail leads to a massive hidden valley of wonders. It contains the technology of a long-vanished civilization, the current race of cat people who have built their own civilization based on strength and violence, monsters created by evolution and science, and the Cavern of the Flame, containing a source of energy that powers all of it. Raft finds himself wrapped up in the intrigues of the cat people, which includes an effort to revive the slowly-dwindling flame: an effort that could destroy the entire valley, and possibly the world.

Valley of the Flame is, at heart, a very standard pulp adventure story. Kuttner is somewhat legendary for being able to write pretty much any genre of story for any market on demand. In this story, I get the feeling that his heart wasn’t particularly in it.

There are, nevertheless, wonderful flashes of brilliance in the story. The Valley is special due to the mystical properties of the flame which, in essence, speed up the metabolism of living things to an unbelievable rate. When the flame was at its full strength, countless generations of felines evolved into the intelligent race of cat people in the span of a few ordinary years outside the valley. Now, even with its power waning, the living things in the valley can effectively perceive months in the span of a single Earth day. This results in wonders to the perception of humans like Raft: boulders floating down at a leisurely pace in freefall, raging rivers move as slow as molasses. Plants which would ordinarily appear stationary instead have diabolical animation:

Those incredible columns seemed to be moving toward him, a giant Birnam Wood malignantly alive. Trees!

For they were trees, not Jurassic cycads, not tree-ferns. He could tell that. They were true trees, but they should have grown on a planet as large as Jupiter, not on Earth.

They were sanctuaries as well, retreats for living organisms, he saw as the trail passed near the towering wall of one. From a distance he had thought the bark smooth. Instead it was literally covered with irregular bumps and swellings.

Vines slid across the trunk like snakes, creeping with a slowness that belied the sudden flash of tendrils as — tongues? — snapped out to capture the insects and birds that fluttered past.

Rainbow flowers glowed on the leafless vines, and a heavy, sweet scent drifted into Raft’s nostrils. From something like a shallow shell that jutted from the trunk a lizard darted out, seized a vine, and carried it back, writhing, to its water-brimming den. There it proceeded to drown the snaky thing and devour it at leisure.

Kuttner has a lot of fun with the idea of super-metabolic processes, though even this never quite reaches the imaginative height of his other works. I found the story enjoyable, but it is not his best work.

One thing about Valley of the Flame bugs me now, though it probably wouldn’t have when I was younger. Raft ends up falling in love with one of the beautiful humanoid cat people, a women named Janissa. Knowing what I know these days about biology, the notion of interspecies romance seems rather creepy, especially species that are not even in the same biological order, four levels more general! Of course, the idea of sexy cat people is not unique to Kuttner, and is found in a lot of fiction. But it’s still weird.

In short: Kuttner’s Valley of the Flame is an entertaining, though rather conventional, pulp adventure story. It will be of most interest to fans of Kuttner’s work. (skullsinthestars.com)

The most recent book of his I’ve gone through is The Well of the Worlds (1952):

The most recent book of his I’ve gone through is The Well of the Worlds (1952):So what can I say about ‘Well? I actually had a hard time getting through the first few chapters, because I found it initially somewhat erratic and unsatisfying, but it picks up significant speed about halfway through (it’s only 125 pages) and I enjoyed it much from then on. It isn’t quite the same caliber as The Time Axis or Destination: Infinity, but it is still an enjoyable book.

The novel starts oddly enough — government agent Clifford Sawyer has traveled to a remote uranium mine to investigate reports of ghosts haunting its lower levels. He first meets with Klai Ford, a lovely young woman with a mysterious past (she doesn’t remember her own past) who is co-owner of the mine. From her, he learns that the other co-owner, a shady old man named Alper, has communed with the spirits in the mine and may have set his sights on having Klai eliminated.

Sawyer meets next with Alper, and events quickly spiral out of control. Alper tricks Sawyer and manages to bring him under his power, but events in the mine thrust Alper, Sawyer and Klai into the extra-dimensional world from which the ghosts originate. Once there, they find a ruling class of immortal and invincible godlike beings, the Isier, who cruelly rule over a society of humans known as the Khom. Also involved are a sub-human but also invincible race of being called the Sseli, who are the sworn enemies of the Isier, and the mysterious Firebirds, the ghosts of the mines, whose connection to the others is not quite clear.

Nevertheless, Alper, Sawyer and Klai find themselves in the middle of a power struggle between the Isier, and they end up in a cycle of temporary alliances and unexpected betrayals that lead inevitably to the secret of the Isier and the possible destruction of their world.

As I noted, the story initially lost me — the characters are quite superficial, especially compared to Kuttner’s other sci-fi works, and the early events such as Alper’s seizing control over Sawyer seemed rather contrived. Even the first descriptions of the extra-dimensional world felt kind of uninspired!

As always, however, Kuttner eventually justified the faith I’ve had in him. The early events set up a wonderful power struggle between the various characters, human and Isier alike, and the twists and turns of the story used the seeming contrivances in very clever ways. The world itself fleshes itself out quite nicely once the primary villianess, the Isier Nethe, really starts her own machinations, and it is intriguing to imagine wicked beings who are genuinely impervious to harm and the implications of this.

Kuttner again draws his inspiration from a scientific idea; in this story, he works with nuclear physics and radioactive decay. The Isier are described crudely as “isotopes” of humanity; this idea sounds somewhat silly at first but Kuttner manages to develop an entire world and history around it.

I couldn’t put the book down while I was reading the final chapters. Though I don’t consider it quite as good as Kuttner’s earlier science fiction, it is still an enjoyable novel with thought-provoking ideas. skullsinthestars.com

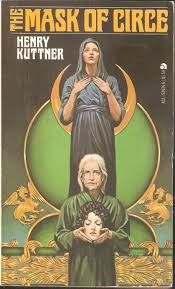

Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore, sci-fi's preeminent husband-and-wife writing team, eased back a bit from earlier years' prolific outputs in 1948, coming out with only four short stories and a short novel. The previous year had seen their sci-fi masterpiece "Fury" serialized in the pages of "Astounding Science-Fiction," and to follow up on that brilliant piece of work, the team switched gears, as it were, and wrote what was in essence an example of hard fantasy, "The Mask of Circe." This tale, which was first published in the May 1948 issue of "Startling Stories," finally got the book treatment it deserved in 1971.

In it, Jay Seward, a modern-day psychiatrist, tells a very strange story over a Canadian campfire. As a result of some narcosynthesis research that he had been engaged in, repressed memories of his had been unearthed, and Seward realized that he was a distant lineal descendant of no less a figure than Jason, of the Golden Fleece and Argonaut fame. And before long, Seward had been mystically transported aboard the Argo herself to the isle of Aeaea, home of the sorceress Circe, and embroiled in a cosmic battle between the warring gods Apollo and Hecate. This story is perhaps one of the most way-out in the entire Kuttner-Moore canon, and for that reason, maybe, the pair thought to give it some grounding in logic and science. Thus, we are given semiplausible theories to explain not only the origin of the Grecian pantheon of gods, but also for the existence of fauns, satyrs, dryads, the Fleece itself, et al. But even with all these attempts at rationalization, the book remains quite an exercise in hard fantasy.

Kuttner and Moore's admiration for the master of these types of tales, Abraham Merritt, is evident not only in the book's Canadian wilderness opening, so reminiscent of the Alaskan wilderness opening in Merritt's 1932 classic "Dwellers in the Mirage," but in the central story itself. In Merritt's "The Ship of Ishtar" (1924), archeologist John Kenton is magically transported aboard the galley of the title and becomes involved in a duel between the Babylonian gods Nergal and Ishtar. Kuttner and Moore do a very passable job, thus, of pastiching an author they admired greatly, and to its credit, "The Mask of Circe" is able to stand on its own, uh, merits. With its limbo-world setting, fantastical characters straight out of Homeric mythology (and no, a detailed knowledge of mythology is NOT a prerequisite before getting into this book), seemingly magical weapons and battling gods, the book almost makes for an hallucinatory, lysergic experience. Anyway, I would also like to advise readers to seek out the 1977 Ace paperback edition pictured above, as it contains no less than 15 beautifully rendered, full-page illustrations by an artist named Alicia Austin that greatly enhance the reading experience. Whichever edition the reader picks up, however, "The Mask of Circe" is guaranteed to provide a few evenings of wonder. Like all the works from Kuttner and/or Moore, I more than highly recommend it! (Sandy, GoodReads)

No comments:

Post a Comment